How to choose your VPN

What is a VPN for, and how do you choose one? Explore the technical and legal aspects of VPNs and learn how to select the right one for your needs.

Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) have become common tools, with a vast range of services and subscription plans available. While purchasing a VPN service has become incredibly easy, choosing the right one is not, especially if you don’t fully understand how a VPN works and what the risks may be.

Before continuing, leave a like!

Here, we’ll explain in simple terms what a VPN does (and doesn’t do), the main risks to consider, and the best criteria, including legal ones, for choosing a reliable provider.

What a VPN does

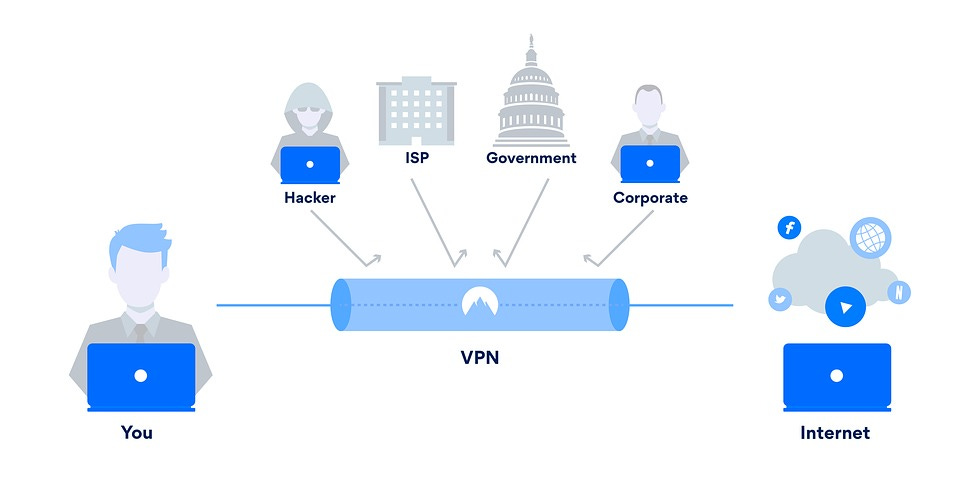

Under normal circumstances, when we browse the internet, our requests for connections are received by Internet Service Providers (ISPs) like Tim, Vodafone, or Fastweb, who then direct them to the target server. This means we are fully transparent to our ISP: they know exactly when we connect, which websites we visit, which devices we use, and even our physical identity.

However, when using a VPN, data is routed through an encrypted tunnel that hides the information packets from the outside world. A VPN essentially acts as a private network that sits between you and your ISP.

A VPN primarily performs three functions:

It changes your public IP address, thereby masking your real IP address.

It encrypts your traffic data.

It prevents your DNS traffic from being visible in plaintext.

One key advantage of a VPN is that it hides your real IP address from third-party observers, effectively separating your identity and geographic location from your online activities.

Because data is routed through the VPN tunnel and encapsulated in encrypted packets, even your ISP won’t know your connection destination—they’ll only know that you connected to a VPN server at a certain time.

In addition to providing privacy from ISPs and external observers, a VPN allows you to bypass geographic restrictions or censorship. For example, a person in Europe who wants to access certain censored Russian news sites could use a VPN server located in Kazakhstan to circumvent these geographical blocks.

A second benefit of a VPN is encrypting data in transit, providing basic protection against hackers, trackers, passive surveillance, and various attacks like man-in-the-middle attacks. This is especially important when using public networks (e.g., municipal Wi-Fi, coffee shops, train stations) where you can't be certain of network security or who might be on the other side.

Finally, using a VPN can also mitigate certain technical vulnerabilities, protecting against threats like SSL stripping and DNS traffic observation.

To summarize, a VPN:

Enhances data privacy from ISPs and third parties, making it more difficult for them to link your physical identity to your online activities.

Increases the security and privacy of data in transit.

Allows bypassing geographical restrictions.

Mitigates some technical risks, such as SSL stripping.

Moreover, a VPN raises the cost of surveillance and identification. Law enforcement agencies do not have infinite resources and time, and in many cases, they may not pursue complex warrants if the effort outweighs the value.

What a VPN does not do

A VPN does not make your browsing more secure.

Although some VPN services, like ProtonVPN, have built-in ad-block and domain analysis features to mitigate the risk of downloading potentially malware-infected content, using a VPN does not protect your device from malware or other types of viruses, nor does it shield you from phishing or social engineering. Always be careful about where and how you browse and what you download. A VPN is not a firewall or an antivirus.

Another common misconception is that using a VPN makes your browsing anonymous. Unfortunately, many online reviews and marketing communications claim exactly this, but it is entirely false.

A VPN separates your identity from your online activities in the eyes of the outside world, but this separation does not equal anonymity. One fundamental aspect of defining a dataset as anonymous is unlinkability—the technical impossibility of connecting different "items of interest" (IOI). Linking IOIs may involve specific actions and identifying data (e.g., an IP address) or between groups of actions. Depending on the extent and detail of the correlations, it may even be possible to infer the identity of the individual.

Since a VPN service merely encrypts and routes data through its private connection, it has the power to collect and store numerous direct or indirect identifying data points that could be used to link IOIs and potentially identify the person to whom they relate.

For example, a dataset containing connection logs with destination, date, and time could lead to the identification of an individual based on their habits. If this dataset also includes directly identifying information, like a registered email address or electronic payment methods, the process becomes much easier.

To summarize, a VPN:

Does not make you anonymous.

Does not eliminate the ability to link your identity to your online actions.

Does not make online browsing more secure (unless using additional services).

Does not affect the tracking capabilities of websites and services (e.g., Meta, Google).

A matter of Trust

Connecting to a VPN means revealing at least your IP address to the service provider, in addition to a series of personal data like email addresses, payment details, usernames, and passwords. Additional data, such as connection date, time, and duration, location, and various metadata, may also be collected by the VPN provider.

The provider, therefore, gains the power to link your identity to your online actions. In effect, the VPN becomes a "man-in-the-middle" with the power to intercept everything you do and identify you at any moment. That’s why it’s crucial to use reliable VPNs.

The VPN provider could thus become the most serious threat to the privacy of your data. A careful selection of a trustworthy provider with the technical ability to protect your data is not only a matter of convenience and functionality but also the first step to reducing risks.

It's essential to remember that many claims by VPN providers are pure marketing: providers that claim not to collect any data or logs are often only telling half the truth. Every VPN will always have at least a technical need to collect and process some logs, if only for security reasons (e.g., DDoS mitigation) or to limit user traffic based on the chosen subscription. There is no such thing as a VPN that truly collects no data.

Using a VPN to mitigate “Data Retention” risks

An important aspect to consider when deciding whether to use a VPN and which one to choose is "data retention" laws.

These laws, which are now almost universal, require ISPs to retain data related to telephone, online, and location traffic for at least a specified period. The goal is to ensure the availability of data and metadata for investigations by authorities.

Typically, data retention laws apply to ISPs, but in some cases—depending on the law or its interpretation—they could also apply to VPN services. This is where things get complicated and a case-by-case analysis is necessary. If the law in the country where the VPN provider is established applies to this service, it could be an issue: the VPN provider would be required to retain and make your data available to authorities for a certain period.

On the other hand, using a VPN could be a way to bypass these laws.

The types of data subject to mandatory retention vary by law but can include IP addresses, location data, timestamps of connections (date, time, duration), IMSI, and IMEI (for mobile), among other things.

It's a very complex topic, but it’s crucial to understand the rules around data retention before choosing a VPN.

In terms of data retention, European countries are very variable: Sweden and Switzerland, for example, limit the obligation of data retention to six months. Nine months for Finland; one year for France, and two for Spain. Italy is the worst, currently at six years!

In Germany, the UK, the Netherlands, Portugal, Austria, Romania, Norway, and Ireland, there are currently no specific data retention laws, so each provider is free to retain (or not) data for as long as they prefer.

Based upon the data retention laws of your country and the laws that apply to the country where the VPN provider is established, you can easily understand if it’s worth using it or not. For example, if you’re located in Italy (6 years), it almost always makes sense to use a VPN established in Germany or Switzerland (or any other country) to minimize the data processed by your ISP and obtain a shorter retention period based on the VPN's country of reference.

Injunctions and gag orders

Another threat to privacy, even when using a VPN, is injunctions from judicial authorities. Requests from governments to access data processed by companies offering VPN services are becoming increasingly frequent.

Proton, for example, reported receiving 6,253 injunctions in 2021, compared to 3,767 in the previous year.

Sometimes, as in the case of WindScribe VPN (Canada), authorities don’t have to try very hard, as they find data stored in plaintext and freely accessible despite the provider's claims to the contrary.

In some jurisdictions, such as the United States, these injunctions may be accompanied by so-called "gag orders"—orders that oblige providers not to disclose information about the access request, thus preventing them from alerting the affected parties, who may then be investigated without even knowing it.

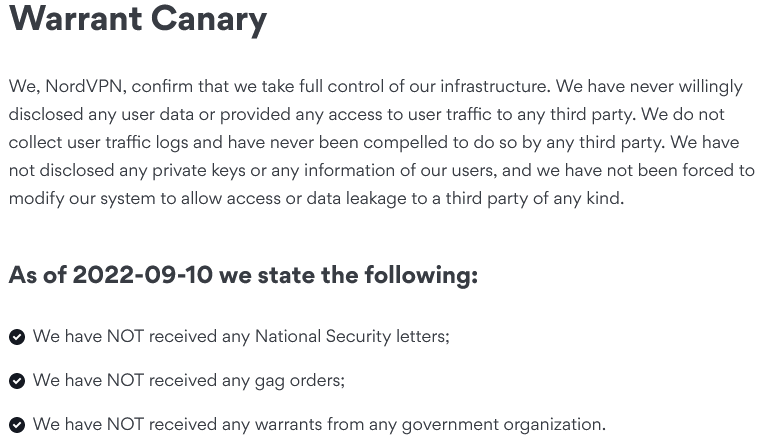

To address these threats, many VPN service providers offer clients periodic reports on received injunctions.

Some go further by using the “Warrant Canary” mechanism: these are permanent messages that remain published online as long as the provider does not receive any gag orders. When the Canary is removed or modified, users will know something is wrong. It’s a kind of fail-safe way to indirectly inform clients of an ongoing investigation.

Criteria for choosing a good VPN

As you’ve seen, the choice depends on many factors. Personally, I like Mullvad and Proton, both of which I find valid. Here are some useful criteria for choosing a good VPN:

Choose a provider that operates outside the 5/14 Eyes.

Avoid jurisdictions with gag orders, like the United States.

Check the logging policies.

Ensure the protocol used is OpenVPN, currently the best and open source.

Avoid providers that ask for more data than is strictly necessary for the service.

Avoid services with advertising.

Avoid services with dedicated IPs; shared public IPs are better.

Check the service's security and privacy policies and transparency.

Prefer providers that offer payment methods like Bitcoin or Monero (even via vouchers).

And remember: never share your VPN account with third parties. While VPN traffic is encrypted, it’s still visible to the provider. This means that if others use the VPN to carry out criminal activities, the provider might receive an injunction to disclose traffic data, which would inevitably include yours as well.